Control or Cooperate?

Jan 31, 2022

FEATURE – Lean Thinking is about voluntary participation, not audits that are meant to ensure compliance. The authors explore the advantages of pursuing cooperation rather than control.

Words: Michael Ballé, Cyril Gras and Daniel Jones

Pick any lean tool. What do you intend with it? Take Just-in-Time, for example. Do you mean to use it to control the amount of inventory you have in your supply chain or to make sure the different parts of the chain cooperate better with each other?

Take time study at a workstation: with it, do you intend to check that the operator is following the standardized work exactly or do you wish to have a conversation with them about their difficulties with the work and the ideas on how to make the job easier?

Don’t dismiss this question too quickly. Kiichiro Toyoda formulated the concept of Just-in-Time as he set out to realize his belief that “the ideal conditions for making things are created when machines, facilities, and people work together to add value without generating any waste.” He conceived methodologies and techniques for seeing waste between lines and processes so that people could collaborate in eliminating it.

Similarly, the andon’s stop-and-call at the sight of an abnormality starts with a check of the standard work. This is not meant to control that the person correctly “follows” standards, but to check there is a common understanding of the standard. This is why lean thinks in terms of loss functions and boundary conditions: “OK or not-OK” is not about someone doing something in the right or wrong way, but about ensure there exists a shared understanding of what is normal vs what is abnormal. This fundamental insight turns the hierarchy from a chain of command to a chain of help – and is a true source of cost reduction, as it progressively eliminates defects and rework.

The origins of management theory are often traced back to Frederick Taylor’s “scientific management”, which aimed to replace every rule-of-thumb practice with “scientifically” determined work instructions. Engineers would observe the work, determine the “one best way” and then ensure worker compliance with these work methods. In the 1920s, this subordination of the people who do the work to the people who design it was further reinforced by the managerial adoption of Weber’s theories on bureaucracy: the vertical chains of command-and-control, punish-or-reward, and promote those who dutifully follow instructions and procedures. Subordination theory (you accept to obey instructions, follow procedures, and be punished or rewarded by your manager for pay) developed the twin components of technocracy (experts design the best system, the rest implement) and bureaucracy (executives give instructions in silos, the rest comply and report). This model became completely dominant from the 1970s onwards, prompted by Milton Friedman’s exhortation for business to only focus on making profits and activist funds’ obsession with controlling executive behavior through outsized financial incentives.

However, at that time, the mainstream view of the firm was Chester Barnard’s looser theory of cooperation. In this approach, the main role of the executive is not to ensure subordination, but to coordinate people’s efforts towards achieving a common goal. This means prioritizing the communication system over the formal organization and securing essential services from members according to their own aims and demands. The set-up should balance effectiveness (getting the job done at lowest cost) with efficiency (making sure the unintended consequences of getting the job done would not become overwhelming by ensuring that each participant finds their own personal benefit in participating).

All but forgotten now, Barnard was very influential in management circles in the 1940s. He is seen as the first proponent of a general theory of collective action and a key influence on Fritz Roethlisberger at Harvard and John Dickson of Hawthorne Studies fame. Barnard was also a mentor to Herbert Simon, a key architect of post-war organization theory. Barnard saw organizations as systems of cooperation depending on the willingness of subordinates to accept the authority of their supervisors, according to the meaning and personal benefits they saw in cooperating with the collective effort.

The cooperative approach was dominant throughout the war years and is obvious in the construction of the great post-war multinational concerns, both public and private. In this perspective, it seems self-evident that the interests of each party must be considered by the whole in order to keep people wanting to be involved, not just forced to do so. In the lean field, cooperation for instance is very visible in the Training Within Industry wartime programs of job instructions, job methods and job relations. Supervisors were rapidly trained to run war industry workshop by teaching them how to better collaborate with workers in their charge.

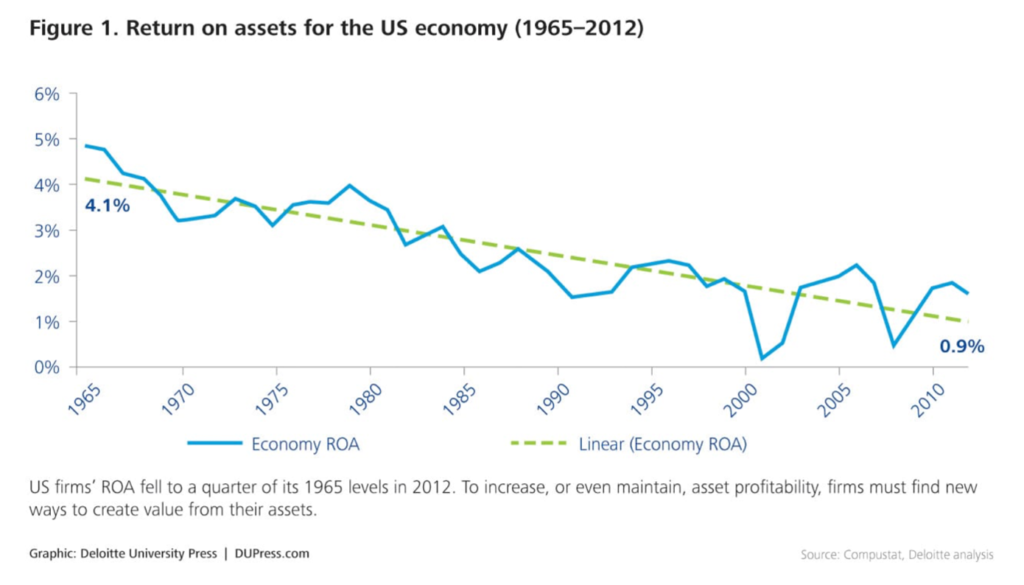

Yet, in the 1960s, at a time of absolute world domination of US businesses, subordination came to the forefront. Peter Drucker was inspired by General Motor’s manage-by-the-numbers approach to formulate his management by objectives theory (still alive and well today in the form of Objectives and Key Results, etc.). Early Boston Consulting Group and Bain consultants would rationalize business lines to focus – scientifically – on the most profitable products exclusively. Later, activist investors became obsessed with agency theory: how to make sure the CEO would work exclusively for shareholders and not for her own benefit, or that of other stakeholders. The answer to that problem was outsized bonuses for CEOs based on shareholder value. Power loves subordination – it’s simple and reassuring. The downside is that it leads to poor outcomes overall, as we can see by the steady fall of company performance measured by Return on Assets:

Subordination and cooperation are always present to some extent in any management system. Individuals, however, tend to focus mainly on one approach or the other. These are very different mindsets:

- Taylorist mindset: in the traditional taylorist mindset, the “system,” scientifically determined, must rule over individual opinion. The aim is to be more productive by avoiding “soldiering” (people’s propensity to do the minimum to get by on the job) and to adopt the “one best way” to do any task, as determined by an outside expert in work study, based on the assumption that no one can do the work and think at the same time.

- “Toyotist” mindset: the constant collaborative search for waste and ways to eliminate it leads to mutually agreed standards, through a rigorous process of Plan-Do-Check-Act to agree whether a suggested improvement really makes things better for all involved. These standards are a basis for further improvement by seeking voluntary contributions to quality and productivity from all employees, all the time. To do so, people are taught self-assessment methods and encouraged to come up with suggestions and participate to work improvement quality circles.

Both approaches offer a path to scaling operations. The taylorist mindset relies on reusable knowledge. What has been optimized somewhere can be standardized and applied in a cookie-cutter fashion to other operations. The focus is on ensuring compliance with the standard and correcting any cause of variation. This method is very useful to grow quickly and replicate processes, particularly in lower-cost areas with less trained people. It is also altogether inflexible and prone to generate massive waste. By contrast, the toyotist mindset is built on reusable learning: rather than replicate the findings, one replicates the learning curve. People are told to start from what they are and, by using lean analysis techniques, solve one problem after the other until they reach the next performance and productivity frontier, which they are tasked to constantly push back through improvement. The key difference here is that, in a lean system, people learn to know their processes in depth and in detail – which also makes a staggering difference to their level of improvement.

The gap between these two mindsets is not trivial and, in practice, depends solely on the manager’s interpretation of the tools – as we mentioned in the opening of this article. For instance, under the lean leadership of its CEO, Aramis Group is fast expanding its capacity to refurbish second-hand cars for resale to promote a more circular economy. It recently built a new auto-reconditioning plant in Belgium, set up along flow principles, and with a lean learning workplace system to support local management’s efforts in solving problems and eliminating waste.

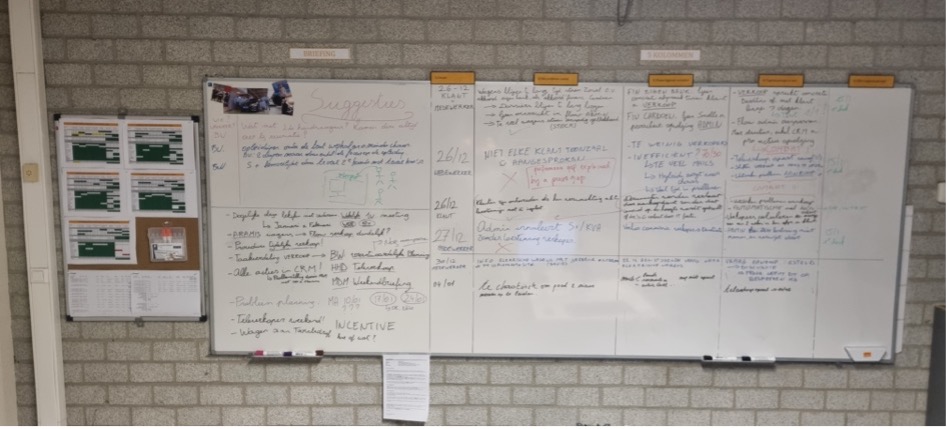

Departments will typically dedicate a room to key indicators, problem-solving boards, weak point management and change management. In the discussion at the workplace with local management, the CEO asked them to use the boards for team self-reflection on how they went about solving problems and to seek new insights – not for additional managerial control of how each person was working.

In a traditional culture of subordination, the manager spontaneously used the boards to lead the problem-solving discussion and get the team to adopt his solution. It takes effort and understanding to resist the temptation of thinking in the team’s stead and coach people into observing and defining the problem, investigating factors and narrowing on probable causes, and then coming up with possible countermeasures. This doesn’t mean relinquishing managerial control as the manager will arbitrate between options if the team can’t settle on a next step, but the aim of the exercise is to give everyone a seat at the table and support discussions to produce new insights and initiatives – not exert one’s authority.

A problem-solving board in Aramis Group’s Cardoen Obeya

Although the tools are often very similar, this radical difference in orientation leads to widely differing outcomes. The constant pressure to comply with rules and roles leads to rigid, red-tape bureaucratic processes whereas the impetus to bring people on board and foster collaboration through mutual trust leads to agile, lean enterprises – with a financial focus on maximizing its base of satisfied customers and Return on Assets, as Nate Furuta reveals of Toyota in his breakthrough book Welcome Problems, Find Success.

The true purpose of any system is not revealed by what people say they want but by what the system does. When you look at any lean or continuous improvement effort, do you see voluntary participation by people to quality and productivity improvements supported by their management? Or do you see audits and controls to make sure the tools are in place and the standards applied?

As the founders of the Toyota Production System saw clearly, systematic waste elimination as well as the ability to respond flexibly to market challenges is only possible through the inclusive involvement of every stakeholder in visualizing work, finding problems, and solving them together. Taiichi Ohno and his followers were famous for posing problems and not answering, letting people figure out their own solutions – then encouraging cross-fertilization by sharing and debating new ideas across functions and sites. As Kiichiro Toyoda first formulated it, the aim is to get people to work together to add value without generating any waste.

As digital tools and systems become ubiquitous, the same dichotomy appears. Is the digital system used for greater cooperation or for stricter control? Is the system enabling people to work more creatively and more productively (better outcomes, less hours spent), or conversely constricting them into narrow, inefficient processes incapable of adapting to local situations and individual cases? There is no permanent answer to the Yin-Yang nature of the control/cooperation balance – the trick is to constantly seek a positive equilibrium. In this, whenever you try and implement a lean technique, ask yourself: “Am I aiming for greater control or deeper collaboration here?”

Now that climate change is widely recognized as an existential challenge for humankind, we need to face the complexity of the problem and find the best way forward. Technocratic (find a silver bullet scheme or technology) and bureaucratic (legislate and control compliance) approaches are being largely discussed, but it’s hard to see how these will deliver without greater engagement and initiative from everyone, everywhere. We believe the lean model is ideally suited for this kind of large, complex challenge, as it teaches everyone to find, face and frame problems in order to form solutions collaboratively. This is how Aramis Group is supporting a more circular economy and doing it in a lean way – offering every employee the opportunity to learn the lean tools and collaborate across departments and countries to come up with less wasteful ways of doing business. These are the kind of grassroots efforts we need to share and replicate in order to touch people’s minds and hearts about climate change and promote real, concrete, practical insightful change.

Control comes naturally to all of us. When faced with a challenge, we naturally try to figure out what to do on our own, answer the question “Who should do what?” and go and tell them. Cooperation starts with asking a different question – “Who should talk to whom?” and how to make this happen. As you teach yourself to ask this second question first, you will learn to shape vastly different answers to your business challenges, working with people to build, new, innovative, and robust solutions.

THE AUTHORS

Michael Ballé is a lean author, executive coach and co-founder of Institut Lean France.

Cyril Gras is Group Head of Kaizen Office at Aramis Auto.

Daniel T. Jones is co-founder of the Lean Movement.

Original Article: https://planet-lean.com/control-or-cooperation/

Stay In Touch.

Subscribe to our newsletter and exclusive Leadership content.